Lancashire - 'Cotton Workshop of the world'

- Andy Robson

- Sep 5, 2022

- 4 min read

Cotton was a hugely important industry for Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries and Lancashire was at it’s centre.

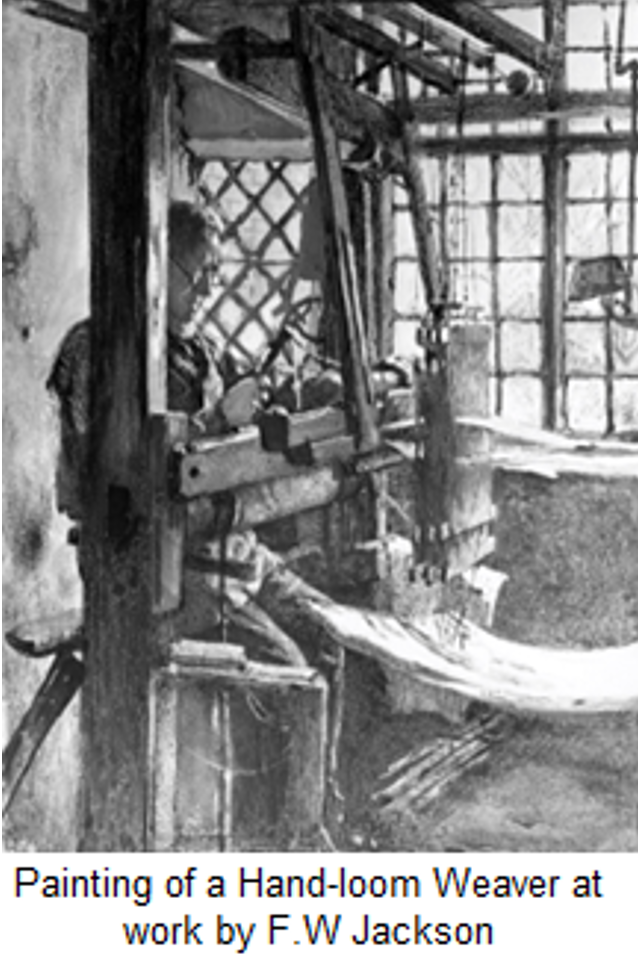

The trade had helped drive the Industrial Revolution during the second-half of the 1700’s, with hand-looms worked as a cottage industry gradually superceded by Mills fitted with first water, then steam powered machinery. By 1825, raw cotton fibre (most of it from the United States) was the largest single import into Britain. The imported raw cotton fibre being spun and woven into cloth in its many Mills and then exported around Britain and the World.

Lancashire had the optimum resources for cotton production; plentiful supplies of fast-flowing, clean water, a damp climate which prevented the cotton fibres splitting during spinning, locally mined coal, and access to the port of Liverpool; which dominated trade with the Americas. The area also had a tradition of wool, linen and fustian production which meant that there was a ready supply of willing workers. At its peak, Lancashire provided 30% of the world’s cotton goods and accounted for over half of Britain’s total exports. Not for no reason was the County known as the ‘Workshop of the World’.

For the County’s traditional and skilled Hand-loom Weavers, however, the introduction of powered cotton mills, which required far less workers for the same output, brought only unemployment and hardship. After 1812, the effects of greater automation were exacerbated by the world-wide economic slump which followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Hand-loom Weavers still accounted for a quarter of the working population of Lancashire as late as 1820 and in 1826 some 60% of such workers in Blackburn were unemployed. That April saw the outbreak of the Lancashire Weaver’s riots, with Mills being attacked and power looms destroyed in a useless bid to halt the march of progress.

The introduction of an improved power-loom in the early 1840’s and the construction of railway lines brought greater investment and many new Mills were opened in the following decades, 68 weaving and 4 combined spinning/weaving works between 1850 and 1870 alone.

The industry however, was characterised by long working hours and low pay. To make matters worse, it went through regular cycles of boom-and-bust that meant uncertainty of employment. The 1840’s, for example, were so difficult that they were known as the ‘Hungry Forties’.

The American Civil War (1861-5) brought about great changes in the industry. A Union blockade of southern ports caused a shortage in raw cotton - The Cotton Famine – that drove many smaller Mills out of business. As the industry recovered following the end of the conflict, economics drove the building of ever larger Mills with thousands of employees; in 1841, the average number of workers in a Lancashire Mill was ‘just’ 193.

In 1870, the first Mill was built by a Joint-Stock Company allowing a delta-step in the finance available to build bigger and more efficient. Row-upon-row of identical looms were packed into textile factories, with a single Weaver operating anything from 4 to 8 of them. It was an incredibly noisy and bustling environment.

The manufacture of Cotton Cloth they involves two distinct processes, Spinning and Weaving. Each of these, however, comprises several phases. Often a 19th Century Mill would specialise in either Spinning or Weaving, though some Mills were large enough to do both.

Spinning Process:

Mixing and Blowing

The cotton fibre arrives in a compressed bale. A mixing and blowing machine is used to unravel the bale, after which any large debris such as leaves or dirt is cleaned out. Finally, the fibre is processed into sheets or ‘Lap’.

Carding

The Lap is drawn through a series of rollers covered with fine layers of teeth. This has the effect of gradually drawing out the fibres into long, parallel strands while also removing fine pieces of debris such as dust. This screening process also has the effect of removing short length fibres (those less than around an inch) which would otherwise create a weakness in the resulting thread. This process was originally done using wooden paddles known as ‘Cards’, hence the name. The resulting long, parallel lengths of fibre are known as ‘Sliver’.

Combing

The Sliver is Combed by drawing fine teeth through it. This has the effect of removing further small debris as well as more short fibres.

Drawing

Between 6 and 8 Slivers are bundled together. These are drawn through rollers to elongate them to several times their original length and so produce a straightened ‘Drawn Sliver’ of uniform thickness.

Roving

The Drawn Sliver is lightly twisted to make it stronger. The resulting thread is called a ‘Roving’.

Spinning

The Roving is further elongated to produce the desired thickness, then twisted (or Spun) into Yarn. This Yarn is wound onto Bobbins to stop it tangling.

Winding

The Yarn is re-wound onto portable Bobbins for transport to Shops or Weaving Mills. These Bobbins can either be ‘Cheese’ (cylindrical) or ‘Cones’ (cone-shaped).

Weaving Process

Warping

The Cheese or Cones are mounted on a Warping Machine. The Yarn is then wound onto ‘Warping Beams’ – with a predetermined length and number of Yarns on each Beam – under constant tension.

Weaving

The powered Looms weave the cloth in much the same way as did traditional hand-weavers, but automatically and much, much faster. The Warping Beams are mounted onto the Loom to provide the length-wise runs of yarns called Warps. Crosswise lengths of yarn, known as Weft or Filling, are then interlaced with the Warps and pushed tightly against previous runs to gradually create the cotton cloth.

After the length of woven cloth has been created, the Warps are separated or ‘Let-off’ from the Warp Beams. The loose cloth is then removed and folded for packing.

Comments